Programming in the Wild West

Brandon Hays

May 16, 2014

Much like revisiting a neighborhood from my youth, when I reflect on my scant few years in software I'm astonished at how much has changed.

This might have also struck you at some point. Perhaps you were even a pioneer in your community's wild west days, huddling in log cabins of your own construction, only to look around now and see yoga studios and gourmet cupcake shops.

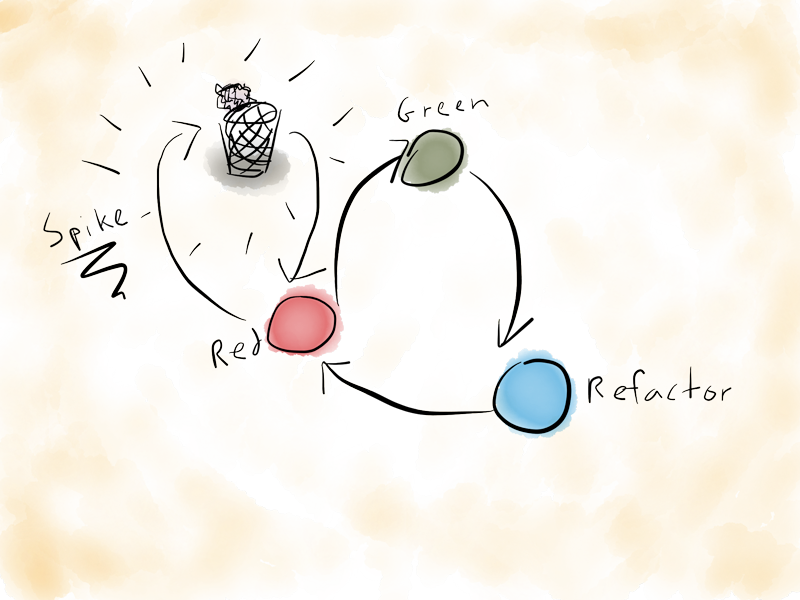

The pattern of how and why this happens is actually related to the way the "red-green-refactor" loop in test-first development helps match our work to our brains. But more importantly, it's reflective of how we can adapt and help our communities as they mature.

First, a journey into the human brain

Studies are revealing that during complex tasks, each of us switches between "open mode", primarily associated with free-form experimentation, and "closed mode", associated with focused execution.

Sarah Mei spoke about this last year at LoneStarRuby, and compared the TDD cycle to moving between these modes. (Starting at 12:20)

The general idea is that at different times, people are better at thinking about the big picture, or zooming in on the details, but not both simultaneously.

This sounds like a simple concept, even obvious, but we ignore it so much that when we actually put the idea into practice, it can be life-altering.

Test-first and open & closed modes

First, I should clarify that this is representative of how I've learned to define and practice test-first development, and others may have different definitions or methods.

For me, this pattern has helped me leverage the strengths of open/closed modes in my brain, because it compartmentalizes times for experimentation and then execution. Much of my own "open mode" experimentation happens via a practice that I don't often hear discussed in TDD circles: spiking code.

The "spike" is where you throw away best practices, testing, and most forms of discipline in favor of discovery. You get out the machete and hack a meandering path from Point A to Point B.

Spiking is the act of figuring out what question you need to be asking. The "red" step is asking the question, then the rest of the TDD process is about answering it. To me, the spiking phase is an essential part of the "open mode" quest to ask the right questions.

The only rule of the spike is that it must be thrown away. You now know where Point B is, and the second trip through using discipline and techniques like TDD will reveal a much straighter path.

But it's an extremely bitter pill: throwing away functioning code is one of the most ego-shattering, counterintuitive things I do as a developer. However, I've learned it's typically faster to subjugate my ego and just delete the code.

The spike clears the "fog of war", shedding light on real-life obstacles in my initial design. Their concrete result is a set of high-level integration tests, from which I can drive out a new implementation in a more direct, point-A-to-point-B way, without having to machete-hack through the jungle.

How this relates to software communities

Software communities, unsurprisingly, behave much like the humans who comprise them.

Yehuda Katz gave a landmark talk at RailsConf, inspiring this post in the first place. He talks about when it's time to move from experimentation mode to shared solutions mode in your community. (Starting at 13:25)

The talk covers several topics, but the main point to me was that software communities have trouble toggling between experimentation ("open") mode and shared solutions ("closed") mode.

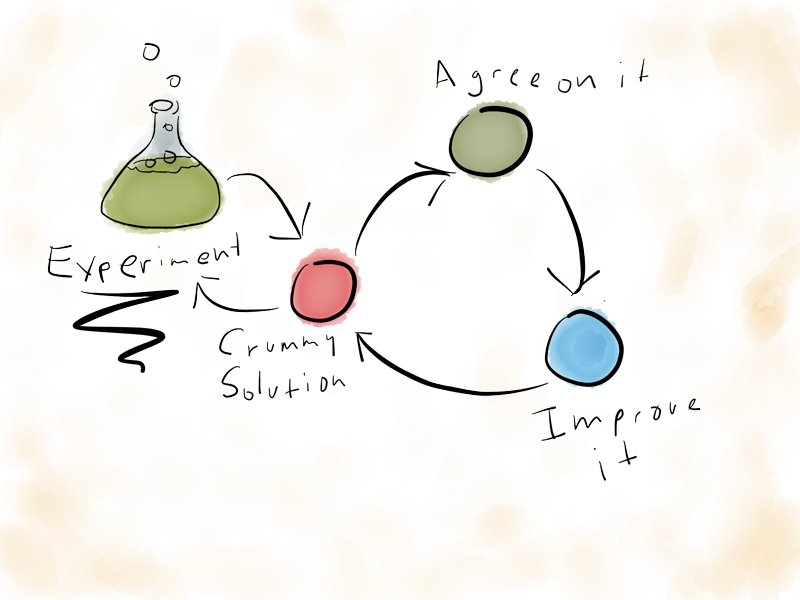

To me, this looks a lot like the test-first cycle above:

Early in a community's maturity, it may be time for a bazaar of different solutions while everyone is simply learning the right questions to ask. What does an authentication solution look like? What about persistence? Security? Code sharing? Scalability? Deployment?

Once a community settles on those few key questions and sees some possible solutions to each, the time comes to get behind existing solutions and improve them. Often, these early projects aren't extremely pleasant to use or well-factored, but can serve to clear that "fog of war" inherent to a new domain. But once the fog is cleared, one or two solutions to a given problem usually gain traction within a community.

"Worse is Better"

When it feels like a community is rallying around a shared set of abstractions, it may be time to delclare it a platform and move from experimentation mode to reaching an agreement. Examples of this in the past include the merging of rival Ruby frameworks Merb and Rails, or the Promises/A+ spec in JavaScript.

In order for this to work, people in a community must be willing to put their energy and focus behind a set of solutions that they don't see as ideal. Maybe they even think they suck. Yehuda used the phrase "worse is better" to describe this. The concept is generally that after the time of experimentation, a community is better served by embracing a comparatively crummy solution and improving it.

There's friction when this change starts happening. Some people feel left behind by the community they helped build. Others see the flaws in existing solutions and want to take their best shot at it, though the time for experimentation has passed. Many may feel that no shared solution could possibly approximate their unique needs.

The good news is that after agreeing on a solution, even if it's a sub-optimal, you can improve the new shared solution, and without much fanfare, there's a new platform for everyone to build upon.

Platforms and scaffolding

Each new layer adds a level of abstraction, so you need to have confidence in the layers beneath you. In software projects, this confidence comes from good tests. In communities, the confidence tends to come from seeing a project in broad use.

We don't spend a ton of time wondering if UNIX is going to crumble beneath us when we're building web applications on top of it, or that the V8 engine in Chrome is just going to stop evaluating JavaScript.

At some point, we declare these to be stable platforms and simply build on top of them without constantly running down to the basement to make sure the furnace didn't explode.

Programming in the Wild West

When I was first learning to program, I was taught a term for people who refuse to leave the "spike" phase of programming. They're called "cowboy coders", often disparagingly. Many of my favorite programmers work in this style, so I use the term hoping it implies no judgment on my part.

Communities have an equivalent type, the "pioneer" who prefers to live in the experimentation phase. Pioneers would rather invent a persistence library or templating engine than spend their day building apps in an existing framework.

When you are in the Wild West, you are, by nature of your presence, a unique and special snowflake. You're the pioneer. You could be the first doctor, the first newspaper editor, or the first blacksmith. All the problems you encounter are by definition novel, and you must survive by your own ingenuity.

Pioneers have much to offer in the "wild west" phase of a developer community. There are few tools, no consensus, and little infrastructure, so there's ample opportunity to contribute in a significant way.

The Rust community seems like a good example of a current-day wild west, leaving many questions yet to be asked, much less answered.

The taming of the West

But after a while, the gold rush has passed, and people have set up Costcos and Pilates studios. The experimentation phase is over, and people have decided on a platform.

Programmers using Rails might remember this starting around Rails 3.0. After that, the big questions were answered, and a few solutions emerged that have evolved into what are essentially just two technology stacks.

The problem occurs when remaining pioneers still want to build a hospital, but there are now plenty of decent hospitals. The community has matured to where offering a lot of alternative solutions start doing more harm than good, creating confusion and decision fatigue.

How do you know a community is reaching the end of the experimentation phase?

- You see articles saying "please no more

x technologytesting libraries/package managers/persistence frameworks" - Consultants specializing in

x technologyproliferate - Both traditional and hacker schools start teaching

x technology - You see job postings at Fortune 500 companies for

x technology x technologyis on the cover of magazines targeted at CEO types

The bitter pill

Remember the bitter pill in TDD, throwing away the spike to embrace discipline and move into closed mode?

As a software community's experimentation phase wraps up and moves into shared solutions, developers have a bitter, ego-shattering pill to swallow, as well. It's the admission that you are not a special snowflake.

If you want to continue working in the community you helped grow, you suddenly have to contend with the fact that many other people moved in and share your same set of problems. It can be brutal to face the idea that a community stands to get greater benefit if you now pour your efforts into shared solutions than into a bespoke, one-of-a-kind tool.

Go West!

Some people have an insatiable desire to pioneer. They are never satisfied with the state of things and want to see the best solution prevail. As they see fences erected and freeways built, they can feel frustrated, as if their freedom is being taken away.

A Rails developer may be tempted to create a better persistence framework, but the community has largely agreed on ActiveRecord and is actively working to make it better.

So what's a pioneering spirit to do? That's the tough part. You can pioneer in ever-smaller niches within your community, swallow the bitter pill of not being a unique snowflake and work on the "worse" solutions, or head west in search of a less mature community in need of doctors and blacksmiths.

You may even find it rewarding to play around with all three options. And the best part is, there is an infinite frontier for programmers. You can always go west, there is always something new to explore if your desire is to chase the sunset into the unknown.

Understanding open/closed modes is good for your software

I am insatiably curious as to why things work, and I'm so glad that Sarah touched on exactly why TDD works in her talk.

I started as a "cowboy coder" and resisted testing for a long time, particularly TDD. It feels restrictive to have to compartmentalize. I already know how to make something work. But it doesn't take me much time to realize how expensive it is to try and do both modes at once, the complexity catches up with me, and I end up wishing I could throw the code in the garbage instead of maintain it.

In TDD, you're dividing the incredibly complex task of writing software along the brain's natural modes. In a designated period of "open mode" thinking, you start to ask the right questions, giving you a concrete result: failing test cases.

You then have a natural break into closed-mode, solution-oriented work, and back again. You let the tests act as a sort of bookmark for your thinking as you toggle between modes, keeping you in context and making you more productive.

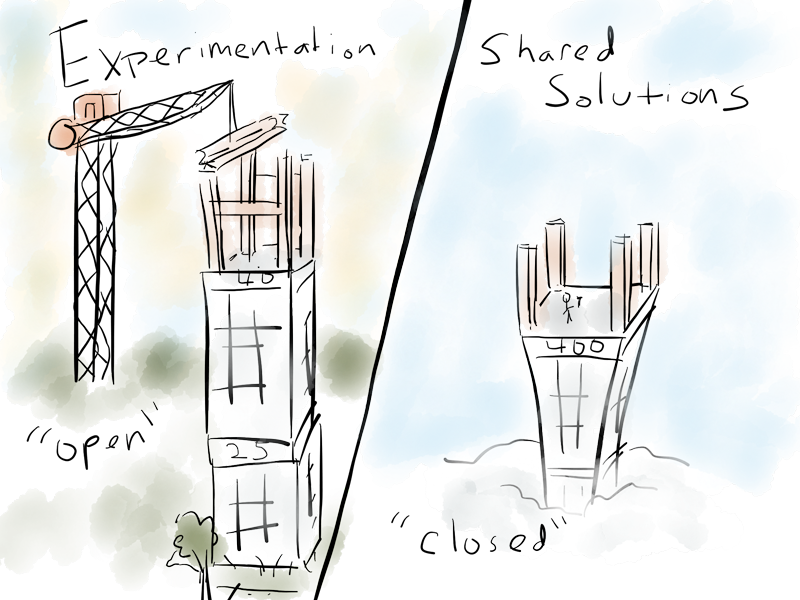

Let's look again at the circular diagrams above. From that perspective, they look positively Sisyphean and don't tell the whole story. In reality, they are the means by which these towering platforms are built, but you have to view the circle from a third dimension to see it:

With good tests, every trip around the loop provides more capabilities on top of a trustworthy codebase. You can keep building without fear of your codebase collapsing under the weight of its own complexity.

Understanding open/closed modes is good for communities

In Yehuda's talk, he plays a couple of videos of Steve Jobs talking about using frameworks to provide a solid platform, so you can build your 5 stories starting on the 25th floor, rather than the 5th floor.

In open source software communities, we can't simply buy into these platforms, we have to agree on them. This happens in the same open/closed cycle: we discover questions by experimenting in open mode, then diving into the closed-mode work of converging on a solution and improving it.

The benefit is an exponential gain in productivity because we aren't exhausting ourselves by keeping 25 floors of scaffolding from collapsing, and instead focusing only on the few flights that comprise our software's unique needs.

At each turn of the loop, a community is establishing a platform for the next go-round. Open source has done a phenomenal job of this over the last 30 years, and the cumulative effect is simply staggering.

The pain of moving into "closed mode"

When Yehuda outlined the difficulty in moving from "experimentation" mode to "shared solution" mode, I felt as if a gong went off in my head, and I suddenly understood much of the friction in the maturing JavaScript community.

I'd contend that we're reaching the end of the JavaScript community's experimentation phase, particularly as it pertains to building client-side applications. We're starting to see people setting up Pilates studios and Costcos. It's entirely possible we'll be talking about ES6 as a watershed moment, the way Rails developers sometimes do about the shift to Rails 3.

This can be rough on the pioneers who got us here. It can also feel constrictive to those who want to build a better version of an existing solution. It's not easy for me, either. I want great tools, not mediocre ones. But if we want the benefits of building on top of platforms instead of our own rickety scaffolding, our responsibility is to embrace imperfect solutions as they get traction, and then improve them.

I'm glad to have the opportunity to participate in the JavaScript community as it starts to converge on "platform-level" solutions. If we'll work together and embrace that we're not "unique and special snowflakes", we can focus on the few floors that actually make our software unique and valuable to other people, so the next generation of developers can start building on the 1000th floor.